Beauty: Greta Magnusson and Peter Eisenman

Some boxes are beautiful; many are ugly. Beauty is not something the world can afford to wait for. We must accept the outcome of our systems and declare whatever occurs as a result beautiful. Beauty can exist only as a retroactive concept, a form of surrender to the inevitable. Like good sportsmanship, beauty is in the graceful admission of defeat. The box happens both by design and by default. A focus on proportions delayed this inevitable conclusion, at least for a while: slender boxes, boxes based on certain proportional systems, even cubes. But no matter how hard we try to reclaim the default as design, all attempts to appeal to the senses suffer defeat in the face of the box’s provable optimum: the outcome of calculation, not of composition. The best box is a box. Only the aesthetic of chance survives, yet another speculation. Only one in 12,487 boxes has a hope of being a beautiful box. The box is architecture’s main achievement. It is also its main trauma – both the result of an extreme effort and of no effort whatsoever. It exists with or without architects. All roads lead to the box.

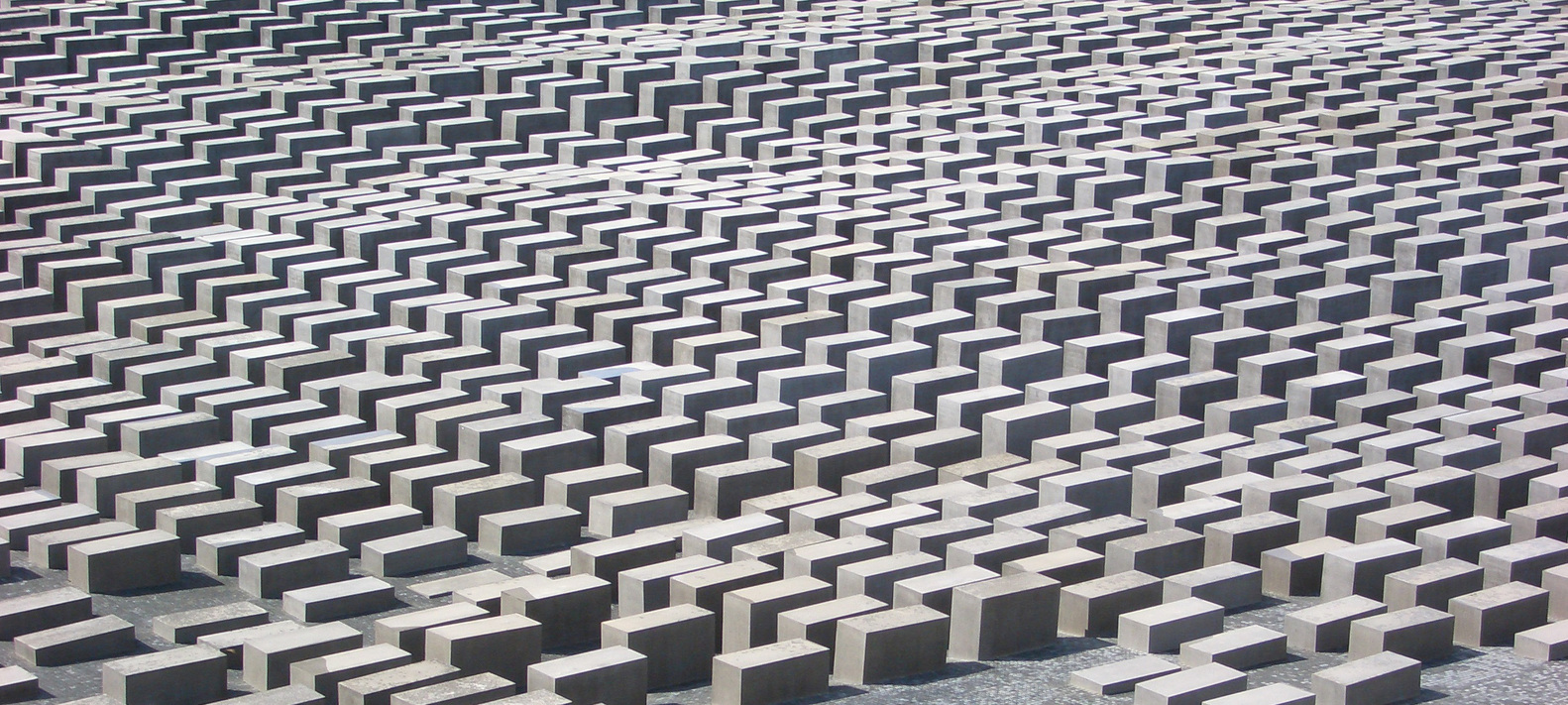

Constructed in 2005, The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe designed by architect Peter Eisenman comprised of two thousand seven hundred and eleven concrete slabs reminiscent of coffins to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust.

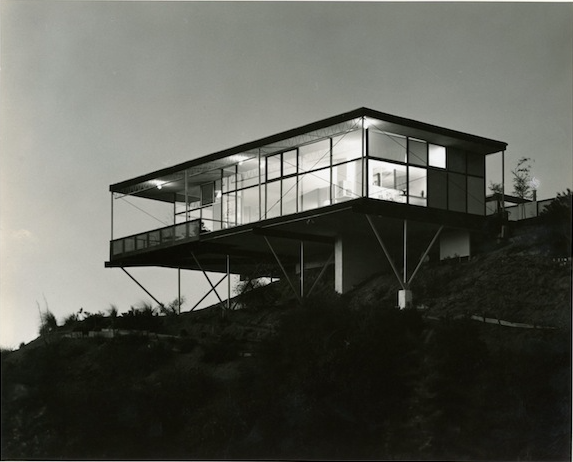

Having emigrated to the United States, celebrated Swedish designer Greta Magnusson opened her famed furniture design practice on Rodeo Drive. Shortly after establishing her store, she began designing homes for clients in the Beverley Hills area. The Hurley House, built in 1958, is one of her most iconic works among the fourteen architectural projects she completed during the course of her career.